The Battle of New Orleans

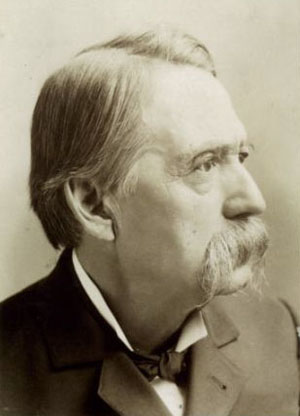

Thomas Dunn English

Here, in my rude log cabin,

Few poorer men there be

Among the mountain ranges

Of Eastern Tennessee.

My limbs are weak and shrunken,

White hairs upon my brow,

My dog—lie still, old fellow!—

My sole companion now.

Yet I, when young and lusty,

Have gone through stirring scenes,

For I went down with Carroll

To fight at New Orleans.

You say you'd like to hear me

The stirring story tell

Of those who stood the battle

And those who fighting fell.

Short work to count our losses—

We stood and dropp'd the foe

As easily as by firelight

Men shoot the buck or doe.

And while they fell by hundreds

Upon the bloody plain,

Of us, fourteen were wounded,

And only eight were slain.

The eighth of January,

Before the break of day,

Our raw and hasty levies

Were brought into array.

No cotton-bales before us—

Some fool that falsehood told;

Before us was an earthwork,

Built from the swampy mould.

And there we stood in silence,

And waited with a frown,

To greet with bloody welcome

The bulldogs of the Crown.

The heavy fog of morning

Still hid the plain from sight,

When came a thread of scarlet

Marked faintly in the white.

We fired a single cannon,

And as its thunders roll'd

The mist before us lifted

In many a heavy fold.

The mist before us lifted,

And in their bravery fine

Came rushing to their ruin

The fearless British line.

Then from our waiting cannons

Leap'd forth the deadly flame,

To meet the advancing columns

That swift and steady came.

The thirty-twos of Crowley

And Bluchi's twenty-four,

To Spotts's eighteen-pounders

Responded with their roar,

Sending the grape-shot deadly

That marked its pathway plain,

And paved the road it travell'd

With corpses of the slain.

Our rifles firmly grasping,

And heedless of the din,

We stood in silence waiting

For orders to begin.

Our fingers on the triggers,

Our hearts, with anger stirr'd,

Grew still more fierce and eager

As Jackson's voice was heard:

"Stand steady! Waste no powder

Wait till your shots will tell!

To-day the work you finish—

See that you do it well!"

Their columns drawing nearer,

We felt our patience tire,

When came the voice of Carroll,

Distinct and measured, "Fire!"

Oh! then you should have mark'd us

Our volleys on them pour

Have heard our joyous rifles

Ring sharply through the roar,

And seen their foremost columns

Melt hastily away

As snow in mountain gorges

Before the floods of May.

They soon reform'd their columns,

And 'mid the fatal rain

We never ceased to hurtle

Came to their work again.

The Forty-fourth is with them,

That first its laurels won

With stout old Abercrombie

Beneath an eastern sun.

It rushes to the battle,

And, though within the rear

Its leader is a laggard,

It shows no signs of fear.

It did not need its colonel,

For soon there came instead

An eagle-eyed commander,

And on its march he led.

'Twas Pakenham, in person,

The leader of the field;

I knew it by the cheering

That loudly round him peal'd;

And by his quick, sharp movement,

We felt his heart was stirr'd,

As when at Salamanca,

He led the fighting Third.

I raised my rifle quickly,

I sighted at his breast,

God save the gallant leader

And take him to his rest!

I did not draw the trigger,

I could not for my life.

So calm he sat his charger

Amid the deadly strife,

That in my fiercest moment

A prayer arose from me,—

God save that gallant leader,

Our foeman though he be.

Sir Edward's charger staggers:

He leaps at once to ground,

And ere the beast falls bleeding

Another horse is found.

His right arm falls—'tis wounded;

He waves on high his left;

In vain he leads the movement,

The ranks in twain are cleft.

The men in scarlet waver

Before the men in brown,

And fly in utter panic—

The soldiers of the Crown!

I thought the work was over,

But nearer shouts were heard,

And came, with Gibbs to head it,

The gallant Ninety-third.

Then Pakenham, exulting,

With proud and joyous glance,

Cried, "Children of the tartan—

Bold Highlanders—advance!

Advance to scale the breastworks

And drive them from their hold,

And show the staunchless courage

That mark'd your sires of old!"

His voice as yet was ringing,

When, quick as light, there came

The roaring of a cannon,

And earth seemed all aflame.

Who causes thus the thunder

The doom of men to speak?

It is the Baritarian,

The fearless Dominique.

Down through the marshall'd Scotsmen

The step of death is heard,

And by the fierce tornado

Falls half the Ninety-third.

The smoke passed slowly upward,

And, as it soared on high,

I saw the brave commander

In dying anguish lie.

They bear him from the battle

Who never fled the foe;

Unmoved by death around them

His bearers softly go.

In vain their care, so gentle,

Fades earth and all its scenes;

The man of Salamanca

Lies dead at New Orleans.

But where were his lieutenants?

Had they in terror fled?

No! Keane was sorely wounded

And Gibbs as good as dead.

Brave Wilkinson commanding,

A major of brigade,

The shatter'd force to rally,

A final effort made.

He led it up our ramparts,

Small glory did he gain—

Our captives some, while others fled,

And he himself was slain.

The stormers had retreated,

The bloody work was o'er;

The feet of the invaders

Were seen to leave our shore.

We rested on our rifles

And talk'd about the fight,

When came a sudden murmur

Like fire from left to right;

We turned and saw our chieftain,

And then, good friend of mine,

You should have heard the cheering

That rang along the line.

For well our men remembered

How little when they came,

Had they but native courage,

And trust in Jackson's name;

How through the day he labored,

How kept the vigils still,

Till discipline controlled us,

A stronger power than will;

And how he hurled us at them

Within the evening hour,

That red night in December,

And made us feel our power.

In answer to our shouting

Fire lit his eye of gray;

Erect, but thin and pallid,

He passed upon his bay.

Weak from the baffled fever,

And shrunken in each limb,

The swamps of Alabama

Had done their work on him.

But spite of that and lasting,

And hours of sleepless care,

The soul of Andrew Jackson

Shone forth in glory there.

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8th, 1815 and resulted in a defeat for the British force attempting to capture the city. The battle was the last major engagement of the War of 1812. It actually took place after the peace treaty ending the war had been signed; the Treaty of Ghent was signed in December 1814 but news of the peace did not reach Louisiana until February.