The Brothers

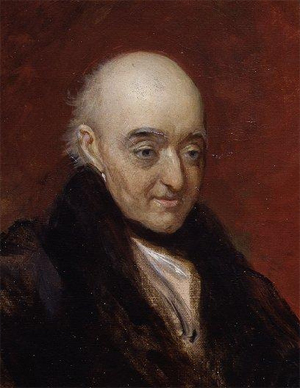

Samuel Rogers

IN the same hour the breath of life receiving,

They came together and were beautiful;

But, as they slumbered in their mother’s lap,

How mournful was their beauty! She would sit,

And look and weep, and look and weep again;

For Nature had but half her work achieved,

Denying, like a step-dame, to the babes

Her noblest gifts; denying speech to one,

And to the other—reason.

But at length

(Seven years gone by, seven melancholy years)

Another came, as fair and fairer still;

And then, how anxiously the mother watched

Till reason dawned and speech declared itself!

Reason and speech were his; and down she knelt,

Clasping her hands in silent ecstasy.

On the hillside, where still their cottage stands

(’T is near the upper falls in Lauterbrunn;

For there I sheltered now, their frugal hearth

Blazing with mountain-pine when I appeared,

And there, as round they sate, I heard their story),

On the hillside, among the cataracts,

In happy ignorance the children played;

Alike unconscious, through their cloudless day,

Of what they had and had not; everywhere

Gathering rock-flowers; or, with their utmost might,

Loosening the fragment from the precipice,

And, as it tumbled, listening for the plunge;

Yet, as by instinct, at the customed hour,

Returning; the two eldest, step by step,

Lifting along, and with the tenderest care,

Their infant brother.

Once the hour was past;

And, when she sought, she sought and could not find;

And when she found,—where was the little one?

Alas, they answered not; yet still she asked,

Still in her grief forgetting.

With a scream,

Such as an eagle sends forth when he soars,

A scream that through the wild scatters dismay,

The idiot-boy looked up into the sky,

And leaped and laughed aloud and leaped again;

As if he wished to follow in its flight

Something just gone, and gone from earth to heaven;

While he, whose every gesture, every look,

Went to the heart, for from the heart it came,

He who nor spoke nor heard,—all things to him,

Day after day, as silent as the grave

(To him unknown the melody of birds,

Of waters, and the voice that should have soothed

His infant sorrows, singing him to sleep),

Fled to her mantle as for refuge there,

And, as at once o’ercome with fear and grief,

Covered his head and wept. A dreadful thought

Flashed through her brain. “Has not some bird of prey,

Thirsting to dip his beak in innocent blood—

It must, it must be so!” And so it was.

There was an eagle that had long acquired

Absolute sway, the lord of a domain

Savage, sublime; nor from the hills alone

Gathering large tribute, but from every vale;

Making the ewe, whene’er he deigned to stoop,

Bleat for the lamb. Great was the recompense

Assured to him who laid the tyrant low;

And near his nest in that eventful hour,

Calmly and patiently, a hunter stood,—

A hunter, as it chanced, of old renown,

And, as it chanced, their father.

In the south

A speck appeared, enlarging; and erelong,

As on his journey to the golden sun,

Upward he came, the felon in his flight,

Ascending through the congregated clouds,

That, like a dark and troubled sea, obscured

The world beneath. “But what is in his grasp?

Ha! ’t is a child,—and may it not be ours?

I dare not, cannot; and yet why forbear,

When, if it lives, a cruel death awaits it?

May He who winged the shaft when Tell stood forth,

And shot the apple from the youngling’s head,

Grant me the strength, the courage!” As he spoke,

He aimed, he fired; and at his feet they fell,

The eagle and the child,—the child unhurt,

Though, such the grasp, not even in death relinquished.